Interview with John Thompson#

Barcelona - February 6th, 2005

We met John Thompson and his wife Suzanne in the hall of their hotel. After exchanging introductions, expressing pleasure at finally meeting after our numerous email exchanges, we started talking about the city. For the interview we went to a bar to eat some tapas before lunch. It was raining when we left the hotel, but it looked like it would turn into a bright day. The interview took place in the tapas bar.

Friends of Guqin: How do you become interested in the guqin?

John Thompson: The answer I’m afraid is a little bit long. On the one hand, during my years in college, I had studied early Western music; on the other hand, I became interested in Asia because I was dratfed into the army and I went to Vietnam. Moreover, I started reading about Asia and, specifically, I read this book ‘The lore of the chinese lutes’ by Robert Van Gulik. From reading that book, I decided that for ancient music the qin would be the best Asian instrument to study, mainly because it is the only non-Western instrument that has a detailed written tradition. So I was interested in it first because of its being ancient, just as I have always liked old Western music. So in fact this was a it was a theoretical interest, as I had never actually heard the music. After I got out of the army and had gone to graduate school, I went to Taiwan to study Chinese and also to find out about the qin. When I started to play it I found I really enjoyed it. So I became interested in the qin theoretically, by reading about it; and I became interested in the actual music by playing it. I liked the sound of the music, but I specially liked the fact that when I played it the sounds were so quiet that I could play only for myself, not having to worry about other people. As I child I had played violin and piano, and always was aware that people didn’t really enjoy listening to me practice. For the qin I didn’t have to worry about that, because nobody could hear me. so I could play and play until I got good. And people could then enjoy listening to it.

FG: What did you feel when you started to play the guqin?

JT: I think that when I started to play, it was the same as when I started to play other instruments. I wasn’t very good so I didn’t enjoy it very much. It was interesting to play, but not really satisfying. With violin and piano there are many good recordings, and so I knew that there was beautiful music, it was just that I couldn’t play it yet. With the qin it was different because I had not been able to find any recordings. Since I could not listen to recordings, I didn’t know how the music sounded until I played it. Without having the reinforcement of hearing great music it was like a kind of experiment. I started in 1976, just after the Cultural Revolution. Even then there still were no recordings available, or perhaps one or two recordings, but not very good recordings. I didn’t start to hear good recordings until the 1980s, maybe five or six years after I had started to play. Then I heard good recordings and said, “Yes, I can see this is beautiful music”. But before that, well, I enjoyed playing it and enjoyed the music, but can’t say I was completely sold on it. It was more like a learning experience, something I enjoyed, but I didn’t yet realize the depth of the music.

I had a similar experience when I studied the Chinese Opera. I had heard some recordings of Chinese Opera and I had gone to a few performances. I thought I didn’t like it all that much. But was interesting to see it, and I knew that it must be beautiful because so many people - intelligent people - said it was beautiful. So I thought maybe I just need to know the language of the music. Music is a kind of international language, but it’s still a language, and so it helps to know something about it, especially if it’s very different from what you are used to. So I started studying Peking Opera. I found a teacher who worked on the production of opera programs for Taiwan television. Every week we would translated a script, then on Friday I would go to see the performance. After I had done that for maybe one month I found that I really liked it. I continued that for about a year and a half, and continued to enjoy it even more. When I was a child I was often told, “You should learn to like that.” Learning the beauty of qin music was at first something like that. After I had been studying for maybe five years I started to find good recordings of the great masters from the 1950s. Then I had a better idea of what I might aspire to.

FG: What musical especially non-Western musical - education did you receive before starting to play the guqin?

JT: At university I studied early Western music, then in graduate school I studied Eastern music. My first Asian instrument was the samisen. The samisen is a Japanese instrument with three strings. It has a skin head, so it’s something like the banjo. I played the samisen in a Japanese musical ensemble in graduate school in the United States. We played music for the Japanese theatre form kabuki. I also studied some other kinds of non-Western music, but none of it had any connection to the qin.

FG: How many qin masters do you have?

JT: I only studied with one master, Sun Yu-Ch’in in Taiwan. I studied with him for two years. Since then you might say my master has been the tablature, because all the music that I’m playing now is music that I have learned from the written music, the tablature. So I’d say that I have had two masters, one was my master in Taiwan, and the other is the tablature.

Suzanne Smith: and Doctor Tong? (Tong Kin-Woon)

JT: I’ve never actually studied playing with Tong. In fact, for six months after I first came to Hong Kong I did actually have another teacher, Tsar Teh-Yun. She must now be about 99 years old, and most of the leading players in Hong Kong are her students. After I studied with her for six months she went to Japan for a while. Meanwhile I was consulting another player in Hong Kong, Tong Kin-Woon. I was not studying qin performance with him. Instead he was helping me to translate texts and discussing the meaning of the music. I’ve never learnt any melodies from him, but he helped me a lot in making the tablature my other master. My understanding of the tablature for the qin is that it’s a student describing the way his master plays a particular melody. What the tablature says is something like, “My master when he plays this melody first puts this finger here, then puts another finger there, and he does this technique and that ornament,” and so forth. It’s not like the Western composition, where someone writes music and you learn to play from it; it’s a description of how a specific teacher played it. So I think of my teachers has having been a series of masters from antiquity, whose music I have learned by studying the descriptions of how they played.

FG: Which qin handbooks have you studied the most?

JT: Well, the focus of my study originally was the Shen Qi Mi Pu, originally published in 1425. After learning the 15 melodies Sun Yu-ch’in taught I began learning music from the Shen Qi Mi Pu. After I had learned all the music in the Shen Qi Mi Pu, and then recorded it, I began studying the third surviving handbook, published around 1491, called the Zheyin Shizi Qinpu. Most of the music is the same music as in the Shen Qi Mi Pu. My first CD was all the music in Zheyin Shizi Qinpu that is not in the Shen Qi Mi Pu. Then I recorded the music in the Shen Qi Mi Pu (eventually six CDs). And then I learnt many pieces from later handbooks, such as Xilutang Qintong, published in 1549; that is probably my third concentration. Then also the Taigu Yiyin published in 1511. Taigu Yiyin is all qin songs. So I’ve been studying these a little bit differently because with qin songs the melody has to go with the song. and so to understand the song you have to translate it. Translating poetry is quite difficult. I’m not comfortable singing a lot of it because I don’t fully understand it. The rhythm comes from the structure of the poetry as well as the structure of the music. But if you are going to follow the structure of poetry, of course you first have to understand the poetry itself.

FG: Is that the reason that so few qin melodies are sung?

JT: No! There are many old qin songs. In fact, in the past there were arguments about this. Should qin music be sung, or should it not be sung? Some people said that when Confucius played he sang, so when we play we should sing. That’s why there were some schools where they sang. Other people say that when you sing and play then it is not so interesting as just the music by itself, so it’s better to just play.

FG: So it’s uncommon to sing.

JT: It’s not so common today. Many qin handbooks from the 15th until the 20th century contained songs. In fact, quite a few 19th century qin handbooks still have songs, so clearly people were often singing them. But in the 20th century they seem to have stopped singing. Occasionally you hear people singing qin songs again, but not very often.

FG: Do you know of any recording of qin songs?

JT: Not of any that only have only songs - I know some recordings where they sing one song or two. However, when I teach I want my students to sing, because I think it’s good way to learn the melodies. When you begin to play you should begin with the simplest melodies, in part so that you can sing them. Moreover if you sing it you not only can remember the melody, you can also learn the pronunciation. I don’t think you need to learn to speak Chinese in order to play the qin, but you should learn at least a little bit, for example, enough to be able to pronounce the words correctly. Singing is good for this.

FG: How difficult is to reconstruct an old qin melody?

JT: How difficult? On a scale of 1 to 10? 1 the lowest, 10 the highest?

FG: Yes, or how much time does it take you to reconstruct one piece?

JT: Well, I’ve been doing it for about almost 30 years now. So it’s different now as compared to how it was at the beginning. The tradition of learning is by copying your teacher. My teacher sat here and played, and I sat there and copied him. Since the music is not written with note values (i.e., the rhythm and meter), it can’t be read like, for example, piano music. When I first started to learn from the written music I studied other people’s reconstructions before I started to do reconstructions by myself. I began with melodies for which there were both recordings and published transcriptions into staff notation, learning from both together. The next step was to learn from a recording where the version being played was a little different from any transcription I could find. I could use the rhythms from the recording and transcription, but had to make adjustments where it was different from the original tablature. In these cases I would study the tablature very carefully, trying to understand the structure of the music, the connection between the written music and the real music. After doing several of these I began to learn directly from tablature, doing melodies that apparently no one had been playing for centuries. Working out the actual notes is usually quite straightforward. I would write the tablature under standard Western staff notation, and work out that, “ok, this figure must be this note”. In this way I write down all notes. Then after I have done that, I start to look for some structures in the music, so then I can assign note values.

From the first I was only doing Shen Qi Mi Pu melodies, but I was not doing it systematically. I would look on one melody and start to work on it. If I was able to learn it then I look into another one. Of the 64 pieces in the ‘Shen Qi Mi Pu’’, four or five seemed quite easy and I did these first. Usually they were short pieces, which were not so complicated. But then when I started on the more complicated ones, some of them were really quite difficult. With the more difficult ones I could spend maybe a month and still not understand it. So I would put it aside and work on a different one, periodically coming back to look at one’s I had found too difficult. With the difficult pieces the basic problem seemed two-fold. First I need to learn to play the notes, then I need to learn to play the melody. But if I didn’t know the melody, how could I play the notes? So in order to learn it, I have to play it. But in order to play it, I have to learn it. With some pieces the melody seemed to come out fairly easily, so this was not a problem. With the most complicated ones, what I occasionally did was play my transcription into a synthesizer, so that I could listen to it and try to sense the melody that way.

Around the time I finished my Shen Qi Mi Pu transcriptions I started using a music transcription program in a computer. Then, I could play back my tentative transcriptions and in this way have another tool for trying to hear the structures in the music. A first, I could spend with the simplest melodies as much as couple of weeks to learn it; now I may be able to do one in a couple of days, or less. But with the most difficult ones it still takes me a lot of time to try to figure it out. But now I have more confidence that, even if it seems very complicated at first, eventually I will find the structures which allow me to feel the music.

FG: Do you write new music for the qin? Or do you know about anyone doing this?

JT: Yes, there are people who write new music for qin, but I have only done a little. The process I’ve used to make new music is to adapt old music materials into new structures. For example, I have taken some traditional motifs and melodic material and rearranged them into a blues structure. I did this with the hope of some time improvising with other musicians. For this I feel I need a structure we would both know. So my first composition was something called China Scholar Blues. I have played this sometimes for Chinese people and their initial reaction is generally thati this is more of my old music. I think this is because, although they haven’t heard it before, they know I play old music that no one else plays and that this old music sounds rather different, so this is probably more of that old music. Also they usually don’t know blues structure, and even if they do it is not so obvious played by itself on the qin. As for the other part of your question, I have met some composers that are composing new music for qin. In China this has often meant something like writing concertos for qin in orchestra. The problem is that here the qin sounds like just any other instrument. But other compositions that take into account the special nature of the qin have been more interesting.

FG: What do you think about the qin’s future?

JT: The future of the qin?

FG: Yes.

JT: I think it is very bright. Actually when I hear this question I first think about the future of the world. In fact the future of the qin is also connected to the future of the world. If we destroy our environment, we can’t live anymore and there will be no more qin. But if we can save the environment I think there are good possibilities for the qin. There are many more people studying it in China and people making good instruments. After the Cultural Revolution almost everyone in China switched to use metal strings (wrapped in nylon). Today it is hard to find people who play with the original silk strings, and I think that has led to quite a different style of music. But I think that now the number of people playing with silk, or at least interested in using silk strings, is increasing. And people outside of China, like in Taiwan, Hong Kong and in New York, are playing with silk strings. I think that in the future there will be two styles of qin play, old styles with the silk strings and new styles with metal strings. I think that in the future there will be more people playing both styles.

FG: In this case of metal string and silk strings, do you think that metal strings can have a negative effect?

JT: I would compare the difference between the silk string qin and the metal string qin with something like the difference between the piano and the harpsichord. The silk string qin is like the harpsichord and the metal string qin is like the piano. The piano and the harpsichord are not enemies, they’re just different. I think the problem today is that so many people don’t realize this difference. In fact, many qin players in China don’t even know about silk strings, or that they are different from metal strings. Originally, the aim with metal strings was to imitate the sound of the silk strings, and to some extent you can do that, but it’s a little bit unnatural. The nature of metal strings makes playing with them rather different. And now people who have learned on metal strings, or played with them for a long time, develop new ways of playing, especially in the way they slide and play the ornaments. They often don’t realize these changes, but I think that eventually they will.

FG: Do you think that the UNESCO acknoledgement of the qin as a cultural and human heritage can help the qin’s future?

JT: I don’t know. In the United States most people don’t seem to know or care what UNESCO is. So maybe in the United States it doesn’t make much difference. In China I think it does. People give it some more respect, so the answer would be yes. I think it’s good in China. But maybe I am confusing government policies with feelings of people.

FG: How is the qin perceived in the United States? Do you feel like a stranger when you play in New York?

JT: The biggest difficulty is that people don’t know what the qin is. Also, the reputation of Chinese music is not very high. Most people think it’s quite noisy and not so interesting. Often it seems to be imitating Western music. It’s difficult in this sense because people don’t realize that all Chinese music is not like that, and in fact the qin is quite different from other Chinese music.

FG: There’s a quote in your website from Curt Sachs about how difficult it is for a Western listener to appreciate the spirituality of qin music.

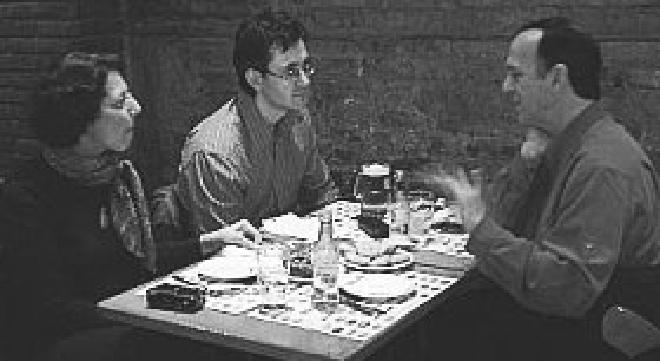

JT: The difficulty I think is not so much in the Westerner as in the environment. You have to listen to the guqin in the right environment. If I were to play the guqin here [we were eating tapas in a bar before lunch - see picture], nobody could appreciate it. But if I play it in a very quiet place, like a library or a church, then I think many people can. In fact, anybody who can appreciate early Western music can appreciate early Chinese music. But you have to hear it in the right environment. The qin has to fit into the environment, it can’t overcome the environment.

FG: Usually, qin melodies have poetic names; so do its section titles. Do you think these titles really mean something?

JT: I see them as being images and allusions, or something like this, not to be interpreted too strictly. It’s not thematic or programmatic, usually. For example, sometimes you can have one piece and it can have a title and each section may have a name, and there may be a specific story. But then another handbook can have almost the same melody but the explanation is completely different. Maybe even the title is different, and the section titles are often different. In some melodies there are specific sounds that are linked to sounds from nature, like thunder, or water flowing over rocks. In such cases it’s programmatic, but usually it is not.

FG: There is a qin melody, “Wild Geese Descending onto a Sandbank”, where you can hear the geese shouting.

JT: Yes, but that’s only a small part of the piece, right?

FG: Yes.

JT: In some pieces I can find that kind of image, and in other pieces I can find other images like that. Also, with regard to Wild Geese Descending onto a Sandbank, I think some other allusions are more important. In Chinese tradition, geese represent a person who is away from home, as the geese migrate every year. And in Chinese literary tradition, geese in the south are usually thinking about their home in the north. Melodies about geese thus represent a desire to go home. So when you listen to this piece, thinking about the desire to go home is more fundamental than hearing what sounds like geese calling out. But how do you represent in music the desire to go home? Maybe you can play a melody from home. In this old music it is very difficult to confirm such references.

FG: How many actual qins do you have?

JT: How may qins do i have? About eight, I think.

FG: Eight qins!?

JT: That’s a complicated question. I have some for sale, because to teach I need to have some instruments to sell. At present, I have two old ones, five made in Chengdu 15 to 20 years ago, including two with electric pickups inside (I have never really used the pickups). Then I still have my first instrument, made about 30 years ago in Taiwan, and the one I brought today for performing, which was made about two years ago in Beijing. Recently I got another one from Beijing. But as I said, I am trying to sell some of them.

SS: Many people have qins just for hanging them on the wall as art objects.

JT: Many people who collect art objects usually want to buy old instruments. So there are a lot of very good old instruments that nobody is playing because rich people own them and hang them on the wall.

FG: And museums…

JT: And museums too. Does any museum in Spain have Qin?

FG: No one, we think.

JT: Does any museum in Spain have a good Chinese art collection?

FG: We don’t think so. Last year we had the Warriors of Xi’an collection, an exhibition of Chinese funerary art.

FG: Have you seen the iron Qin?

JT: I’ve seen the iron qin in Smithsonian Museum. Is that the one you mean?

FG: Yes.

JT: In fact, I have played it. It’s not on display, only in store room, but once when I visited there they let me try to play it. It didn’t make very much sound. It’s made from iron not for the sound, but just for art. I suggested to them making a recording, but they seemed skeptical. I’ve also seen but not played two ceramic qins in the National Palace Museum in Taiwan. The National Palace Museum is the biggest Chinese art museum, and they have two ceramic qins. They also have an eighth century qin.

SS: Did you play those qins?

FG: No, no, but I’d like to.

JT: Not yet!

FG: Qins are not available here, so the only possibility is to purchase them online, but they’re expensive.

JT: If you want an instrument that sounds pretty good it would probably cost at least 1000 dollars, without shipping.

FG: Is the crafting of a silk string qin any different from a metal string qin?

JT: It should be built quite a lot different. Even if the instrument is not good you can get sound with metal strings. Metal strings are tighter, putting more pressure on the body, so the top board has to be thicker. Also metal has more mass, so they don’t vibrate as widely as the silk strings playing the same pitch. So the bridge on a metal string qin can be lower; so if you put silk strings on one of these instruments the silk will vibrate against the wood, making a buzzing sound.

FG: Do qins really need strings?

JT: Well, there’s an inscription in my website accompanying a picture of a man sitting in the countryside with a stringless qin next to him. The inscription says something like, with the sound of nature, what need is there to put strings on the qin? Because the qin music is the sound of nature and you already have the sound of nature, then you don’t need to play the qin. So yes, you don’t need strings to appreciate the qin.

FG: What are the influences of Confucianism and Daoism in guqin music?

JT: It’s hard to say what the real influences are in terms of music. It’s easy to say what the influences are in terms of the titles, so I can only talk about that with certainty. In theory, the Confucian influence is the idea of playing the qin in order to become a better person in society. If you play the qin and you follow the rules of the qin, then you will also follow the rules of society and be a good citizen and serve your fellow man. As for Daoism, the aim is only to follow the Dao. So maybe you don’t really care so much about the world. But you know that if you live a detached life following the Dao, and play the qin with this attitude, then it should be beneficial for the world. This kind of influence is of course very difficult to describe, and even more impossible to measure.

FG: Ok, that’s all!

SS: Big questions!

After the interview we continued talking, indeed, we talked throughout the whole lunch and also when we were heading to the hotel where John would show us the qin he brought for next Tuesdays lecture. We were also surprised when we saw the Qin. We were also surprised when we listened to it as John played it, and how he played it. Its sound and the way it was played were very artistic. John also let us play it. It was wonderful.

The rain stopped before we had lunch. Even with the wet morning, it was a bright day. Thanks John and Suzanne, see you next time!